Posts

Five Practical Lessons for Serving Models with Triton Inference Server

Triton Inference Server has become a popular choice for production model serving, and for good reason: it is fast, flexible, and powerful. That said, using Triton effectively requires understanding where it shines—and where it very much does not. This post collects five practical lessons from running Triton in production that I wish I had internalized earlier.

Choose the Right Serving Layer

Not all models belong on Triton. Use vLLM for generative models; use Triton for more traditional inference workloads.

LLMs are everywhere right now, and Triton offers integrations with both TensorRT-LLM and vLLM. At first glance, this makes Triton look like a one-stop shop for serving everything from image classifiers to large language models.

In practice, I’ve found that Triton adds very little on top of a “raw” vLLM deployment. That’s not a knock on Triton—it’s a reflection of how different generative workloads are from classical inference. Many of Triton’s best features simply don’t map cleanly to the way LLMs are served.

A few concrete examples make this clear:

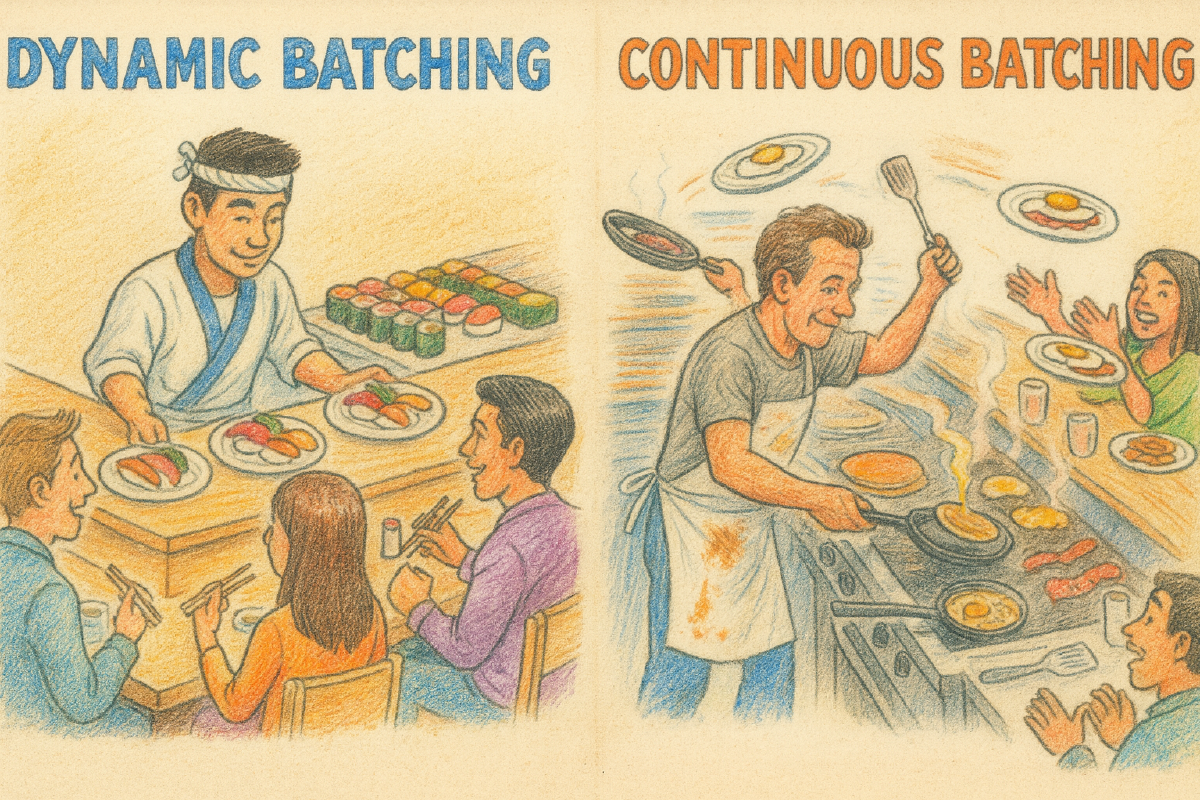

- Dynamic batching → Continuous batching Triton’s dynamic batcher waits briefly to group whole requests and then executes them together. This works extremely well for fixed-shape inference. LLM serving, on the other hand, benefits from continuous batching, where new requests are inserted into an active batch as others finish generating tokens. While this is technically possible through Triton’s vLLM backend, it is neither simple nor obvious to operate.

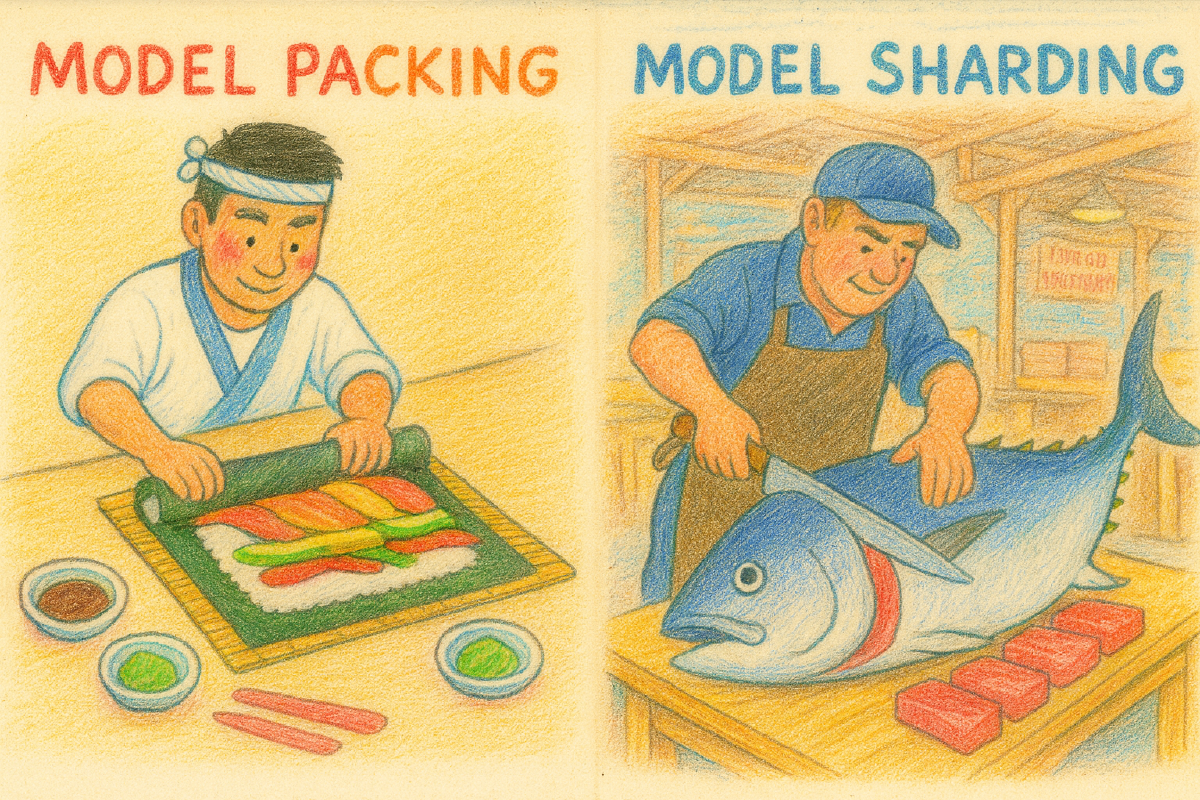

- Model packing → Model sharding Triton makes it easy to pack multiple models onto a single GPU to improve utilization. LLMs rarely fit this model. Even modest models tend to consume an entire GPU, and larger ones require sharding across GPUs or even nodes. Triton doesn’t prevent this, but it also doesn’t meaningfully help.

- Request caching → Prefix caching Triton’s built-in cache works by storing request–response pairs, which is very effective for deterministic workloads. Generative models instead benefit from caching intermediate state, such as KV caches keyed by shared prompt prefixes. This is a fundamentally different problem and one that LLM-native serving systems handle far more naturally.

In short, I’ve consistently found it dramatically simpler to deploy vLLM directly and immediately benefit from continuous batching, sharding, and prefix caching than to layer Triton on top and wrestle with configuration to achieve similar behavior.

Protect Latency with Server-Side Timeouts

Dynamic batching is Triton’s killer feature. By buffering requests for a short, configurable window and executing them in batch, Triton improves hardware utilization and eliminates a large amount of client-side complexity.

There is, however, an important footgun: by default, Triton will not evict queued requests.

Under load, it is entirely possible for Triton to accumulate a backlog while clients time out and move on. If max_queue_delay_microseconds is not configured, those abandoned requests can sit in the queue and eventually execute, consuming resources while newer requests wait their turn.

The result is perverse but common:

- Triton spends time processing requests the client has already given up on.

- Latency increases as the queue drains stale work.

This problem is especially acute when using the Python backend. While some native backends can detect client cancellation, the Python backend largely leaves this responsibility to user code. Once a request reaches your execute() method, it will usually run to completion unless you explicitly check for cancellation.

If you care about latency—and you almost certainly do—server-side queue timeouts are not optional.

Keep Client Libraries Minimal

Triton requires clients to know model names, tensor names, shapes, and data types. Exposing this directly to application developers is unpleasant, so providing a small client wrapper is usually worth it.

Where things go wrong is when that wrapper grows ambitions.

I’ve seen (and built) client libraries that try to be helpful by adding retries, backoff, or other resilience features. In practice, this often backfires. Retrying requests that failed due to overload or invalid inputs can amplify traffic precisely when the system is already struggling, turning a transient slowdown into a self-inflicted denial-of-service.

Which is not to say don’t use retries, but rather don’t make them invisible, and allow callers to identify and be identified when retry logic needs to be revistied.

My recommendation is simple: keep client libraries boring. Let them handle request construction and nothing more. Implement retries and error handling at the call site, where the application has the necessary context and observability to do the right thing.

Leverage Triton’s Built-in Cache

Triton’s request–response cache is easy to overlook, but it can be surprisingly effective, especially in cloud environments. GPU instances often come with far more system memory than is otherwise used, and allocating a few extra gigabytes to caching can spare your GPU a significant amount of redundant work.

This is not a blanket recommendation—many workloads won’t benefit—but it is worth experimenting. Watching cache hit rates alongside queue depth can quickly tell you whether caching is helping and whether a particular client is generating unnecessary duplicate traffic.

Prefer ThreadPoolExecutor for Client-Side Parallelism

On the client side, I’ve found that the simplest way to issue parallel inference requests is also the best one: use a thread pool.

In CPython, socket I/O releases the GIL. Since Triton’s HTTP client is primarily I/O-bound, this makes ThreadPoolExecutor an effective and straightforward choice:

def infer(inputs):

return model_client.infer(inputs=inputs)

with ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=8) as pool:

results = list(pool.map(infer, batch_of_requests))

This approach has a few nice properties:

- The client does not need to implement batching logic.

- Triton’s dynamic batcher can aggregate requests across threads and even across clients.

- Concurrency is naturally bounded, providing a form of backpressure.

Any Python work inside infer remains serialized, which turns out to be a feature rather than a bug: it prevents the client from overwhelming the server while still allowing efficient parallel I/O.

Conclusion

Triton is a powerful serving system, but it is also opinionated. It works best when its abstractions line up with the workload you are trying to serve.

For classical inference workloads, Triton’s batching, scheduling, and caching are hard to beat. For LLMs and other generative models, purpose-built systems like vLLM tend to be a better fit. Understanding this distinction—and configuring Triton defensively when you do use it—goes a long way toward building reliable, low-latency inference systems.