Posts

The AI-Powered 10-Minute Habit That Taught My Kid to Read (And Made Me a Better Dad)

built a system to teach my kid to read, using a free program called Anki for the “planning” and AI to make content that would lure him in.

built a system to teach my kid to read, using a free program called Anki for the “planning” and AI to make content that would lure him in.

t worked, he and I enjoyed it immensely, he reads fluently (though mechanically). Along the way I observed and learned a great deal about learning and teaching, young kids, or my young kid. That’s what I want to share with you today. In particular ,

I’d like to

t worked, he and I enjoyed it immensely, he reads fluently (though mechanically). Along the way I observed and learned a great deal about learning and teaching, young kids, or my young kid. That’s what I want to share with you today. In particular ,

I’d like to

- Give you a little background on the tech and science I used to do this (but just the basics)

- Share what I actually did, and my intuitions for why I did them

- Share what I learned in process.

- Point at how we as parents and teachers can use AI to teach kids.

Anki and spaced repetition

nki is a free program that implements “spaced repetition”, which is a technique to memorize things. Both are then based on the psychological “testing effect”, which is a concept in learning psychology that states that it’s easier to memorize something by trying to remember it as opposed to rereading it.

nki is a free program that implements “spaced repetition”, which is a technique to memorize things. Both are then based on the psychological “testing effect”, which is a concept in learning psychology that states that it’s easier to memorize something by trying to remember it as opposed to rereading it.

nki (and similar programs) let you input what you want to learn, and have study sessions. Just like using flashcards to study. Anki’s killer feature is that you can score, with numbers, how well you remembered something (4=perfect, 1=not at all), and Anki will remember the statistics.

nki (and similar programs) let you input what you want to learn, and have study sessions. Just like using flashcards to study. Anki’s killer feature is that you can score, with numbers, how well you remembered something (4=perfect, 1=not at all), and Anki will remember the statistics.

nki then uses fancy math (an algorithm) to calculate what you should study tomorrow, to maximize the amount of learning you get for the time you invest. Or to minimize the amount of time you need to spend to learn something.

nki then uses fancy math (an algorithm) to calculate what you should study tomorrow, to maximize the amount of learning you get for the time you invest. Or to minimize the amount of time you need to spend to learn something.

Getting a kid’s attention

y son was about four years old when we started. He did not care about spaced repetition, or compounding effects of learning, or daddy’s fancy algorithms. He did like colourful pictures and cuddles.

y son was about four years old when we started. He did not care about spaced repetition, or compounding effects of learning, or daddy’s fancy algorithms. He did like colourful pictures and cuddles.

e had some wall charts with colorful letters and things that started with them, but they were kind of tame and they certainly didn’t get much of his mental real estate. I had a sense that if I could make things that were weird and delightful and surprising, he’d let them in or at least pay attention.

e had some wall charts with colorful letters and things that started with them, but they were kind of tame and they certainly didn’t get much of his mental real estate. I had a sense that if I could make things that were weird and delightful and surprising, he’d let them in or at least pay attention.

’ve always been good with weird and surprising, but am on a good day aesthetically anemic and could never visualize my ideas in a palatable way, much less do hundreds of variants that all looked great. That’s where AI really stepped in here, for each of the 26 letters I got enough variants to throw out the useless ones and keep the best ones for my boy.

’ve always been good with weird and surprising, but am on a good day aesthetically anemic and could never visualize my ideas in a palatable way, much less do hundreds of variants that all looked great. That’s where AI really stepped in here, for each of the 26 letters I got enough variants to throw out the useless ones and keep the best ones for my boy.

Emotional Anesthesia: Building Confidence Through Memorization

think memorization is awesome—especially for kids. Memorization is like anesthesia for insecurity: you can’t think “I can’t” if you don’t even get the chance to think, because you already memorized whatever it is you were going to think about.

think memorization is awesome—especially for kids. Memorization is like anesthesia for insecurity: you can’t think “I can’t” if you don’t even get the chance to think, because you already memorized whatever it is you were going to think about.

think kids (and adults) are naturally curious and want to learn and succeed. But then we beat into them that they’re lazy, or dumb. Someone laughs at them. Dad loses patience. The teacher scolds them for not paying attention. And now it’s: “I can’t.”

think kids (and adults) are naturally curious and want to learn and succeed. But then we beat into them that they’re lazy, or dumb. Someone laughs at them. Dad loses patience. The teacher scolds them for not paying attention. And now it’s: “I can’t.”

ho wants to fight with their kid even more? That’s exhausting—and sad. So instead of fighting them and their self-limiting beliefs, let’s just skip over that whole part of the brain that’s making them feel “I can’t.”

ho wants to fight with their kid even more? That’s exhausting—and sad. So instead of fighting them and their self-limiting beliefs, let’s just skip over that whole part of the brain that’s making them feel “I can’t.”

ow? With memorization. Memorization is targeted emotional anesthesia. We memorize things—small things—and then, when we need them, we don’t even notice they’re there because they’re already memorized. The brain pulls up what it knows before there’s time to feel anything—certainly before the body tenses and the “I can’t” shows up. (This apparently follows from Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory, so I’m not just ranting.)

ow? With memorization. Memorization is targeted emotional anesthesia. We memorize things—small things—and then, when we need them, we don’t even notice they’re there because they’re already memorized. The brain pulls up what it knows before there’s time to feel anything—certainly before the body tenses and the “I can’t” shows up. (This apparently follows from Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory, so I’m not just ranting.)

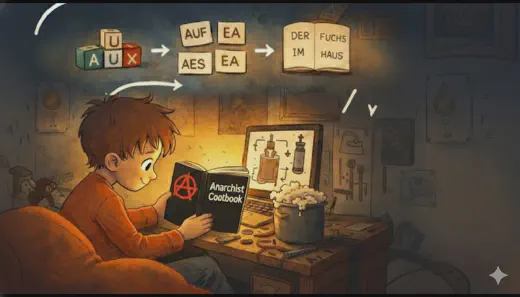

irst letter forms, then diphthong sounds, then whole words. Sentences stagger, then flow, and one day they’re reading The Anarchist Cookbook and learning to make high explosives in Mom’s favorite pot. Sorry, Mom.

irst letter forms, then diphthong sounds, then whole words. Sentences stagger, then flow, and one day they’re reading The Anarchist Cookbook and learning to make high explosives in Mom’s favorite pot. Sorry, Mom.

The Emotional Turn (The Real Discovery)

o far I’ve told you theory, my thoughts on memorization, what spaced repetition is, that Anki is a program that does spaced repetition, and that I made engaging pictures with AI so that we could learn letters. But what did this actually look like?

o far I’ve told you theory, my thoughts on memorization, what spaced repetition is, that Anki is a program that does spaced repetition, and that I made engaging pictures with AI so that we could learn letters. But what did this actually look like?

put those pictures I made in Anki, each day Anki would pick a few new ones, and a few that we needed to review according to its algorithm. Then we’d look at a picture, I’d ask my son “what is that” and he’d say “Igloo” or “Dog” or “Worm”, then I’d ask him what letter it was and he’d say “I” or “D” or “I don’t know” or squirm around and shriek.

put those pictures I made in Anki, each day Anki would pick a few new ones, and a few that we needed to review according to its algorithm. Then we’d look at a picture, I’d ask my son “what is that” and he’d say “Igloo” or “Dog” or “Worm”, then I’d ask him what letter it was and he’d say “I” or “D” or “I don’t know” or squirm around and shriek.

f he didn’t know at all I’d press 1, if he knew it perfectly I’d press 4 and 2 or 3 for the stuff in between. Anki would put on the next item until we got through them. Sessions would last 5 to 10 minutes tops, and when they did go over I’d stop them and configure Anki to do less work or more easy stuff.

f he didn’t know at all I’d press 1, if he knew it perfectly I’d press 4 and 2 or 3 for the stuff in between. Anki would put on the next item until we got through them. Sessions would last 5 to 10 minutes tops, and when they did go over I’d stop them and configure Anki to do less work or more easy stuff.

e did it every day, my son and I. “Bo na’aseh Buchstaben,” he’d say. Half Hebrew, half German. “Let’s do letters.” I’d sit on the orange beanbag in his room, with Anki on my laptop. Sometimes he’d sit on my lap right away, sometimes he’d hang naked off his bunkbed, his ballsack swinging in front of my face in the cool Berlin morning air.

e did it every day, my son and I. “Bo na’aseh Buchstaben,” he’d say. Half Hebrew, half German. “Let’s do letters.” I’d sit on the orange beanbag in his room, with Anki on my laptop. Sometimes he’d sit on my lap right away, sometimes he’d hang naked off his bunkbed, his ballsack swinging in front of my face in the cool Berlin morning air.

don’t know why, but for the ten minutes a day we’d learn together, the holy spirit would possess me and I was filled with infinite patience. No matter what my son did — squirm, jump, hang naked off his bed dangling his balls in my face — I just let him be, waited, hugged him and gently nodded him back when he was ready. It was our comfy, intimate, happy time together. It almost never happened that I got frustrated in that time.

don’t know why, but for the ten minutes a day we’d learn together, the holy spirit would possess me and I was filled with infinite patience. No matter what my son did — squirm, jump, hang naked off his bed dangling his balls in my face — I just let him be, waited, hugged him and gently nodded him back when he was ready. It was our comfy, intimate, happy time together. It almost never happened that I got frustrated in that time.

Shifting the Optimization Target: From Memory to Affirmation

ids aren’t workers, we’re not trying to optimize their learning productivity (the school’s productivity is another matter). One day I realized how uncharacteristically patient I was being, and how enabling and nice that was for my son.

ids aren’t workers, we’re not trying to optimize their learning productivity (the school’s productivity is another matter). One day I realized how uncharacteristically patient I was being, and how enabling and nice that was for my son.

e may have outgrown the humor of my funny pictures, but he kept coming back for the warmth and intimacy, and the validation of getting it right. And I thought: I don’t need to optimize for memorization, which is what Anki tries to do. I can skew the system for fun instead. I had no deadline. No exam. We were doing this for our own pleasure.

e may have outgrown the humor of my funny pictures, but he kept coming back for the warmth and intimacy, and the validation of getting it right. And I thought: I don’t need to optimize for memorization, which is what Anki tries to do. I can skew the system for fun instead. I had no deadline. No exam. We were doing this for our own pleasure.

nd so I did, I set up Anki to mostly show us material my son knew very well. I made trivially easy cards to study,

nd so I did, I set up Anki to mostly show us material my son knew very well. I made trivially easy cards to study, 1+1=? and then Eins plus Eins ist?, so that he might see he has 20 units of work, and plough through 18 of them in 2 minutes and feel like a genius. That only 2 of 20 cards had new information, or “learning value” was fine, is fine. For our purposes, we were optimising retention and joy, so that we reinforce the habit and the feeling that “I can do it”.

ver time, not only did my son learn to read (and also got very good at arithmetic), he learned about learning. He’d struggle reading a sentence and get upset, and I’d remind him that a few months ago he couldn’t recognise most of the letters, and that he did the work, so that now he can read.

He accepted that, and lives with the knowledge that if he puts in the work he will get the reward, which I think is the bigger educational achievement even than learning to read.

ver time, not only did my son learn to read (and also got very good at arithmetic), he learned about learning. He’d struggle reading a sentence and get upset, and I’d remind him that a few months ago he couldn’t recognise most of the letters, and that he did the work, so that now he can read.

He accepted that, and lives with the knowledge that if he puts in the work he will get the reward, which I think is the bigger educational achievement even than learning to read.

Recap and future

feel immense satisfaction with this whole project. I love that my son can read, that “it worked”, the emotional bond we built. I value the learning skills he picked up, and the learning skills I learned from learning about learning.

feel immense satisfaction with this whole project. I love that my son can read, that “it worked”, the emotional bond we built. I value the learning skills he picked up, and the learning skills I learned from learning about learning.

ooking back, seeing my son in school with his reading skills and confidence in his ability to learn, I think:

ooking back, seeing my son in school with his reading skills and confidence in his ability to learn, I think:

- Making the AI pictures was fun for me, and super engaging for my son — it did open the door

- Having a few very different versions of each letter (Apple, Ape, …) helped him not “overfit” and actually learn the letters

- The emotional “peace” and my own patience were critical for making this successful. My son was drawn to and will remember the cuddles, not the act of learning.

- The framework of spaced repetition was a good starting plan for curriculum planning, and was enriched by:

- Keeping things short, under 10 minutes per learning session

- Eventually optimising for “winning” and building confidence, even at the cost of less learning per session

- Adding trivial learning cards, just to reinforce that winning

did this project in 2023-2024, my son was in kindergarten, and I was excited to bring this into the classroom, but could not figure out a way. The teachers wouldn’t be able to manage multi-user sessions of Anki, teaching each child how to use it, etc. And the kindergarten management were also not amenable to innovation.

did this project in 2023-2024, my son was in kindergarten, and I was excited to bring this into the classroom, but could not figure out a way. The teachers wouldn’t be able to manage multi-user sessions of Anki, teaching each child how to use it, etc. And the kindergarten management were also not amenable to innovation.

ech has evolved so fast in the last two years, that I think getting this into classrooms is or will soon be feasible. The two blockers were usability, independent usability by children, and sufficient reliability and maturity so that teachers are freed and empowered, instead of required to fill in a support role.

ech has evolved so fast in the last two years, that I think getting this into classrooms is or will soon be feasible. The two blockers were usability, independent usability by children, and sufficient reliability and maturity so that teachers are freed and empowered, instead of required to fill in a support role.

he other blocker is regulatory and cultural, the willingness of the regulator and parents to allow their children’s learning statistics and behavioural patterns to go to some company’s cloud. Perhaps in the U.S., but this seems unimaginable in Germany.

he other blocker is regulatory and cultural, the willingness of the regulator and parents to allow their children’s learning statistics and behavioural patterns to go to some company’s cloud. Perhaps in the U.S., but this seems unimaginable in Germany.

ut the models are getting smaller, and small enough that we can literally “put them in a box” that doesn’t connect to the internet. And yet, as they get smaller, they are smarter, and it’s easy to imagine a voice interface that kids can use, that can manage auth and be set onsite, and simple agentic workflows that unstick a child that gets off the path. Maybe not today, but I think, soon, and it’s exciting.

ut the models are getting smaller, and small enough that we can literally “put them in a box” that doesn’t connect to the internet. And yet, as they get smaller, they are smarter, and it’s easy to imagine a voice interface that kids can use, that can manage auth and be set onsite, and simple agentic workflows that unstick a child that gets off the path. Maybe not today, but I think, soon, and it’s exciting.